Understanding the history and implications of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Decision

In Part 1 of this four-part series, I provided a historical overview of how the U.S. dealt with the issue of abortion from its founding in 1776 up to the issuance of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the Roe v. Wade case in 1973. In addition, I also provided a summary of the major abortion laws and abortion-related court decisions that occurred in the U.S. – and a summary of the various methods that were used to induce abortions – during that same time period.

In this Part 2, I will review the details of the Roe v. Wade decision – and explain why many felt that the decision was a ticking time bomb from the moment it was released.

In Part 3, I will explain why the Dobbs decision has raised concerns among a wide variety of groups throughout the country about the possible revocation of other previously recognized rights.

And in Part 4, I will describe how various states have chosen to deal with the issue of abortion in the post-Roe v. Wade era – and review how the Dobbs decision may impact the upcoming mid-term elections and the 2024 presidential election.

********************

Author’s Note

I believe it is almost impossible to understand the Roe v. Wade decision without understanding what was going on in U.S. society – and in the U.S. Supreme Court – in the years leading up to that decision. For those of us who lived through those years, many of the events that took place during that time period are etched in our minds forever.

Throughout the 1960s, we practiced hiding under our desks at school as a way to protect ourselves against a potential nuclear attack from the Soviet Union. In 1962, our concerns about such an attack grew even stronger as the U.S. and the Soviet Union faced off against one another over the latter’s placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba – and the U.S. imposition of a naval blockade around the island.

In the years leading up to Roe v. Wade, here are some of the U.S. Supreme Court decisions – and some of the other events – that set the stage for that decision:

- February 28, 1960: The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the federal government can bring civil actions against state officials who were discriminating against African Americans (U.S. v. Raines).

- June 19, 1961: The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that oaths that required anyone to declare belief in “the existence of God” were unconstitutional (Torasco v. Watkins).

- June 25, 1962: The U.S. Supreme Court held that it was unconstitutional to hold organized prayer sessions in public schools (Engle v. Vitale).

- March 18, 1963: The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that indigent defendants were entitled to have free counsel appointed to represent them in criminal cases (Gideon v. Wainwright).

- November 22, 1963: U.S. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

- March 9, 1964: The U.S. Supreme Court protected freedom of the press with regard to political reporting (New York Times, Inc. v. Sullivan).

- July 2, 1964: Segregation was formally abolished in the U.S. via the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

- February 21, 1965: Malcolm X was assassinated.

- June 7, 1965: The U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a Connecticut law that banned the use of contraceptives by married couples on the grounds that the law was an unconstitutional invasion of privacy (Griswald v. Connecticut).

- March 24, 1966: The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that poll taxes are illegal (Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections).

- June 13, 1966: The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that police must inform suspects of their rights before questioning them (Miranda v. Arizona).

- June 12, 1967: The U.S. Supreme Court declared that all laws banning interracial marriage are unconstitutional (Loving v. Virginia).

- October 2, 1967: Thurgood Marshall was sworn in as the first African American Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

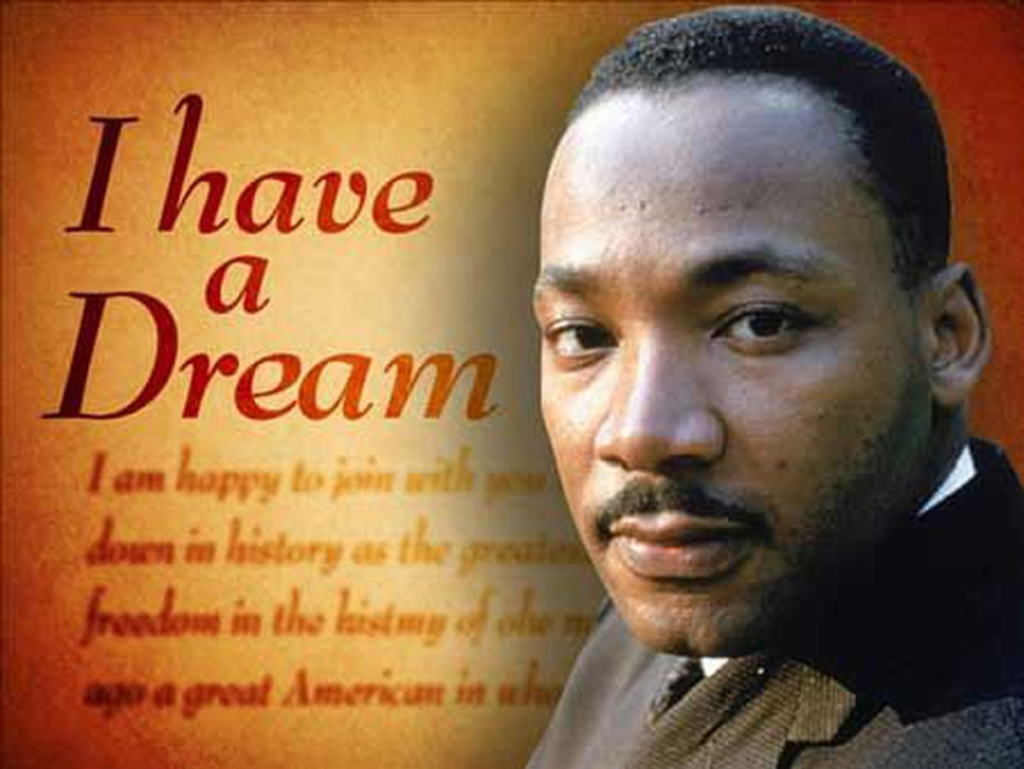

- April 4, 1968: Martin Luther King was assassinated.

- June 6, 1968: Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated.

- November 14, 1968: Yale University announced that it was going to start admitting women as undergraduate students.

- June 23, 1969: Warren E. Burger was sworn in as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

- December 1, 1969: The first draft lottery since World War II was held in the U.S. (My number came up 332 and my roommate, the late Joe Cerretani, came up #4 – numbers that markedly changed both of our lives forever).

- March 13, 1970: Hawaii became the first state to legalize abortion – but its law only applied to residents of the state.

- April 11, 1970: New York State legalized abortion – and did so without any residency requirement.

- November 22, 1971: The U.S. Supreme Court declared a state law unconstitutional on the grounds that it discriminated against women (Reed v. Reed).

- March 22, 1972: The Equal Rights Amendment was passed by the U.S. Senate – and sent to the states for ratification.

The times leading up to the Roe v. Wade decision were tumultuous. Old rules and traditions were tossed aside – and new ones were formed – at a very rapid pace.

As Bob Dylan succinctly noted in 1964, “The Times, They Are A-Changing.”

*****************************************

Roe v. Wade

The Roe v. Wade case concerned an 1854 Texas statute that banned abortion in that state except in cases where it was necessary to save a woman’s life. By the time the case wound its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, abortion was already legal in four states: Alaska, Hawaii, New York State, and Washington.

Norma McCorvey, a Texas woman in her early 20s, had sought to terminate an unwanted pregnancy in her state but was unable to do so.

In 1970, two Texas attorneys – Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington – filed a lawsuit on behalf of McCorvey and all other women “who were or might become pregnant and [who] wanted to consider all options.” In order to protect her identity, McCorvey was listed as “Jane Roe” in the lawsuit.

The lawsuit claimed that the Texas statute in question violated McCorvey’s rights under the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments.

The named defendant in the lawsuit was Henry Wade, the District Attorney of Dallas County, which is where McCorvey lived.

In June 1970, a three-judge panel for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas ruled that the Texas statute that banned abortions was unconstitutional because it violated a woman’s constitutional right to privacy that was implied in the Ninth Amendment and extended to states via the Fourteenth Amendment’s “due process” clause.

Despite this ruling, the District Court refused to provide injunctive relief to McCorvey – which eventually led to her having the baby and putting it up for adoption.

Immediately after the District Court’s decision, both parties appealed the outcome to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. In addition, McCorvey requested that because of the urgency of the matter, the case be “fast-tracked” to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Roe v. Wade was first argued before the U.S. Supreme Court on December 13, 1971. Because of concern about the rationale behind the District Court’s decision – and disagreement among the justices as to how to proceed – the Supreme Court requested that the case be reargued the following term.

On October 11, 1972, the Roe v. Wade case was reargued before the Supreme Court. And on January 22, 1973, the Texas anti-abortion statute was struck down via a 7-2 decision that was based on the application of the Ninth Amendment’s “fundamental right to privacy” – and the extension of that right to states via the Fourteenth Amendment.

As set forth in the Supreme Court’s decision, states were not allowed to place any restrictions on abortions during the first trimester of pregnancy.

That same decision, however, acknowledged that states could place reasonable restrictions on second-trimester abortions – and that they could continue to ban all abortions during the third trimester (Note: Both of these restrictions were subsequently eliminated in the Supreme Court’s 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey).

Some excerpts from the Roe v. Wade decision will help to underscore its frailty:

- The Constitution does not explicitly mention any right of privacy. In a line of decisions, however, going back perhaps as far as Union Pacific R. Co. v. Botsford, 141 U. S. 250, 251 (1891), the Court has recognized that a right of personal privacy, or a guarantee of certain areas or zones of privacy, does exist under the Constitution. In varying contexts, the Court or individual Justices have, indeed, found at least the roots of that right in the First Amendment, Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U. S. 557, 564 (1969); in the Fourth and Fifth Amendments, Terry v. Ohio, 392 U. S. 1, 8-9 (1968), Katz v. United States, 389 U. S. 347, 350 (1967), Boyd v. United States, 116 U. S. 616 (1886), see Olmstead v. United States, 277 U. S. 438, 478 (1928) (Brandeis, J., dissenting); in the penumbras of the Bill of Rights, Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. at 484-485; in the Ninth Amendment, id. at 486 (Goldberg, J., concurring); or in the concept of liberty guaranteed by the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment, see Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U. S. 390, 399 (1923). These decisions make it clear that only personal rights that can be deemed “fundamental” or “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty,” Palko v. Connecticut, 302 U. S. 319, 325 (1937), are included in this guarantee of personal privacy. They also make it clear that the right has some extension to activities relating to marriage, Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S. 1, 12 (1967); procreation, Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U. S. 535, 541-542 (1942); and contraception, Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. at 453-454; id. at 460, 463-465.

- It should be sufficient to note briefly the wide divergence of thinking on this most sensitive and difficult question. There has always been strong support for the view that life does not begin until live birth. This was the belief of the Stoics. [Footnote 56] It appears to be the predominant, though not the unanimous, attitude of the Jewish faith. [Footnote 57] It may be taken to represent also the position of a large segment of the Protestant community, insofar as that can be ascertained; organized groups that have taken a formal position on the abortion issue have generally regarded abortion as a matter for the conscience of the individual and her family. [Footnote 58] As we have noted, the common law found greater significance in quickening. Physician and their scientific colleagues have regarded that event with less interest and have tended to focus either upon conception, upon live birth, or upon the interim point at which the fetus becomes “viable,” that is, potentially able to live outside the mother’s womb, albeit with artificial aid. [Footnote 59] Viability is usually placed at about seven months (28 weeks) but may occur earlier, even at 24 weeks. [Footnote 60] The Aristotelian theory of “mediate animation,” that held sway throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Europe, continued to be official Roman Catholic dogma until the 19th century, despite opposition to this “ensoulment” theory from those in the Church who would recognize the existence of life from the moment of conception. [Footnote 61] The latter is now, of course, the official belief of the Catholic Church. As one brief amicus discloses, this is a view strongly held by many non-Catholics as well, and by many physicians. Substantial problems for precise definition of this view are posed, however, by new embryological data that purport to indicate that conception is a “process” over time, rather than an event, and by new medical techniques such as menstrual extraction, the “morning-after” pill, implantation of embryos, artificial insemination, and even artificial wombs. [Footnote 62].

- To summarize and to repeat:

1. A state criminal abortion statute of the current Texas type, that excepts from criminality only a lifesaving procedure on behalf of the mother, without regard to pregnancy stage and without recognition of the other interests involved, is violative of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

(a) For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester, the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgment of the pregnant woman’s attending physician.

(b) For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health.

(c) For the stage subsequent to viability, the State in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgment, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.

***************************************

The Ticking Timebomb Problem

The fundamental problem with the Supreme Court’s decision in the Roe v. Wade case is that it was based on a “right” that is not enumerated anywhere in the U.S. Constitution.

Instead, this so-called “fundamental right to privacy” was previously described as a “penumbral right” – which is a term used by those who believe that there are rights derived, by implication, from other rights that are explicitly protected in the Bill of Rights.

Although the term “penumbral rights” was mentioned in several Supreme Court decisions dating back to 1916, the term achieved prominence when Justice William O. Douglas used it in the Griswold v. Connecticut decision to explain that “specific guarantees in the Bill of rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.”

While some applaud the concept of “penumbral rights,” several legal scholars have severely criticized the concept – and rejected the notion that there are any guaranteed rights beyond those that are explicitly stated in the Constitution.

Many of those same critics took umbrage with the Roe v. Wade decision.

For example, John Hart Ely, a constitutional scholar and professor at Yale Law School who supports legalized abortions, wrote, “What is frightening about Roe is that this super-protected right is not inferable from the language of the Constitution, the framers’ thinking respecting the specific problem in issue, any general value derivable from the provisions they included, or the nation’s governmental structure. Nor is it explainable in terms of the unusual political impotence of the group judicially protected vis-a-vis the interest that legislatively prevailed over it. And that, I believe … is a charge that can responsibly be leveled at no other decision of the past twenty years.’”

Edward Lazarus, who describes himself as “utterly committed” to legalized abortion, describes the Roe v. Wade decision as follows: “Roe borders on the indefensible. … Justice Blackmun’s opinion provides essentially no reasoning in support of its holding. And in the … years since Roe‘s announcement, no one has produced a convincing defense of Roe on its own terms.”

Conservative judge Robert Bork wrote, “Both Roe and [Planned Parenthood v.] Casey are, in fact, crass violations of the rule of law; they are not rooted in any conceivable interpretation of the Constitution, and have nothing to do with ‘constitutional terms.’”

Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox noted, “The Justices read into the generalities of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment a new ‘fundamental right’ not remotely suggested by the words.”

In essence, the Roe v. Wade decision was based on a concept rather than on a specified right in the U.S. Constitution – or a specific federal statute that enumerates the right set forth in the decision.

As such, the right to abortion set forth in Roe v. Wade has been a “ticking time bomb” from the moment the decision was first announced on January 22, 1973.

And now that time bomb has exploded – and created chaos and uncertainty across the country in terms of whether – and where – women will be able to obtain abortions in the future.

While much anger and blame are being directed at the members of the current U.S. Supreme Court who chose to overturn Roe v. Wade, there are others who deserve as much – if not more – anger and blame for what they did not do to protect a woman’s right to have an abortion.

Take, for example, the first two years of the Obama presidency – when Democrats had control of the House, the Senate, and the White House.

How easy it would have been to pass a federal statute that codifies the rights set forth in Roe v. Wade and its progeny. Had that occurred, it is unlikely that the right for women to obtain abortions would have been upended by the current Supreme Court.

And what about all the states that failed to pass similar laws that would protect the right for women to have abortions within their boundaries? Had they done that, women in those states would still be able to obtain abortions in those locations.

But none of those things happened – and we now find ourselves in a situation where a woman’s ability to have a safe and legal abortion will be left up to the legislatures and governors of individual states.

****************************************

Stay tuned for Part 3 which will be published later this week.

As I will explain in more detail in more detail in Part 3, there are other reasons why the overturning of the Roe v. Wade decision has left it up to the individual states to decide what restrictions, if any, they will place on abortions within their respective jurisdictions. As of now, however, there are no national policies or standards regarding abortion – a situation that has not existed during the lifetime of more than two-thirds of all Americans.

********************

As usual, feel free to comment on this post by registering at Register – Trials & Truths (trialsandtruths.us). And feel free to email questions about this post – or any other post – to [email protected].

******************************

#Abortion#RoevWade#SCOTUS

#USSupremeCourt

#Dobbs

#DobbsvJackson

As I website owner I believe the content here is real great, thanks for your efforts.

Bork was a “strict constructionist”.

I agree with this analysis. What is abortion doing in a document that gives us Freedom of Speech, worship, etc.?

Don’t forget standing concept, “Capable of repetition yet evading review.”

This was excellent. Loved the historical context, too.

Kilgore,

Glad you liked this post – and I really do think that it’s hard to understand the Roe v. Wade decision without taking into consideration the prior court decisions and events leading up to it. In Part 3, I’ll also explain how the Supremacy Clause in the U.S. Constitution and the Tenth Amendment will affect what happens now that Roe v. Wade has been overruled.